Overcoming Adversity and Redefining ‘Girl Power’ in the Japanese Corporate Sphere

ISSUE 20 | Conversations with Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada

🧭 Introduction: The Complex Landscape of Female Leadership in Japan

Japan is clearly lagging behind in the global movement toward gender diversity in leadership positions. According to the 2025 Global Gender Gap Report, Japan ranks 118th out of a total of 148 countries.1 By comparison, the UK is ranked 4th overall – a whopping 114 places ahead of Japan.2 The proportion of female executives at companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s (TSE) top-tier Prime section stood at 18.4% as of July 2025.3 While this represents a 2.3 percentage point increase from 2024, the figure still falls short of the government’s targets.4 A prior article written by former SIIFIC intern Lily Thomas, titled Who is Investable and Why, expands on the gender inequity amongst CEOs in Japan, citing that only 2% of funding goes toward female founders.5 To learn more about this article, click here.

It must be noted, however, that while the numbers are low (18.4%) for female executives in larger companies listed on the TSE, this statistic changes when looking at smaller businesses (SMEs), where in 2007 women made up 26.6% of business owners or managers.6 This data, while insightful, is significantly outdated. Although a substantial gender gap in leadership positions persists, it’s reasonable to assume these numbers have evolved since 2007.

Given this context, I wanted to gain insight into what life is like for Japanese women in leadership positions. Last week, alongside fellow intern Airi Shinobe, I had the pleasure of interviewing two inspiring female professionals in Osaka through SIIFIC.

Mitsuki Bun: Founder of Losszero

Mitsuki Bun is the founder and CEO of Losszero, an innovative social enterprise based in Osaka dedicated to tackling Japan’s food waste crisis. Founded in 2018, the company addresses a critical environmental issue: Japan wastes tonnes of food annually – approximately 4.64 million tonnes in fiscal 2023 – in part due to its notoriously strict expiration date regulations (shoumi kigen).7

Losszero has developed a circular economy model that aligns perfectly with SIIFIC’s wellness equity mission. The company purchases mottainai (waste) food products—items that remain perfectly safe and nutritious but cannot be sold through conventional retail channels due to approaching expiration dates or cosmetic imperfections. Not only are these products redistributed to consumers at significant discounts (typically 40-60% off retail pricing) but customers are also given a description of the item, information regarding its producer, and reasons why the product was at risk of being wasted.

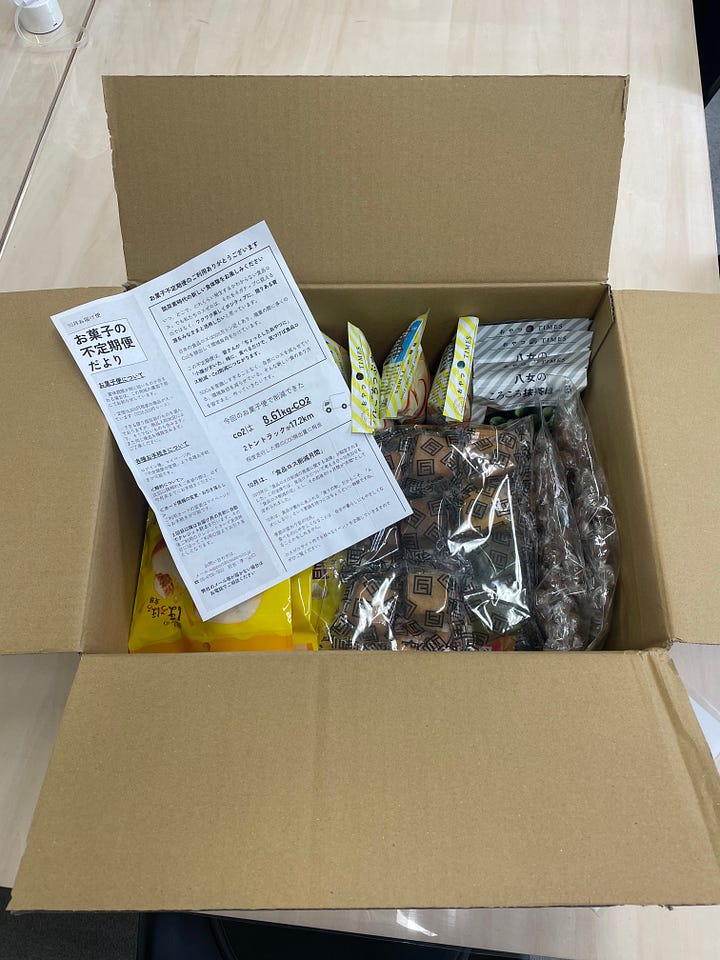

The company’s product range has expanded to include premium snacks, staple items like rice and noodles, and specialty products such as organic jams and traditional Japanese sweets. Consumers can purchase individual items or opt for curated monthly subscription boxes (which SIIFIC’s office has maintained since 2024 as part of its sustainability initiatives).

With a predominantly female workforce and numerous partnerships with food manufacturers, Losszero has successfully diverted a substantial amount of food from landfills. Beyond the environmental benefits, the company enhances nutritional equity by making quality food more affordable, perfectly aligning with SIIFIC’s mission of making wellness accessible across different socioeconomic groups.

You can access Losszero’s website here.

Yumiko Terada: Champion of Female Leadership in Legal Entrepreneurship

Yumiko Terada embodies SIIFIC’s commitment to transformative leadership and gender equity through her multifaceted career. As co-partner of ARCUS partners, an all-female legal team, she experienced great challenges in Japan’s male-dominated legal industry. Beyond her role as SIIFIC’s General Counsel, Terada serves as an external auditor and director for multiple organisations, including Losszero where she provides governance oversight that supports its social mission.

As a visiting professor at Kobe University, she mentors the next generation of legal professionals with particular emphasis on encouraging female students to pursue entrepreneurial paths. Her international experience includes participating in the prestigious International Visitors Leadership Program in the US, where she gained valuable insights on global approaches to gender equality in professional settings. Throughout her 20-year legal career, Terada has consistently worked to create more inclusive spaces in Japan’s corporate environment, directly aligning with SIIFIC’s core values of accessibility, equity, and sustainable community development.

You can access Yumiko Terada’s profile here.

🌟 SIIFIC’s Commitment to Gender Diversity

While SIIFIC’s mission centers on wellness equity, this is a concept that extends beyond physical health. The firm’s approach encompasses organisational diversity as well. The company’s co-leadership structure, with both female and male co-founders, demonstrates a strong commitment to gender diversity in Japan’s corporate sphere. This approach is backed by research showing that gender-balanced investment teams generate 10–20% higher returns than single-gender teams, with similar performance benefits seen in venture capital partnerships and portfolio companies with diverse leadership.89 Understanding the barriers that women like Bun and Terada face in reaching senior business positions remains crucial to advancing this mission.

🚧 Barriers for Women in Japanese Workplaces

Both Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada highlighted an array of obstacles that they have needed to overcome over the course of their respective careers.

👩💼 Mitsuki Bun’s Journey: From Young Mother to CEO

From an early stage in her career, Bun realised how the corporate sphere asked more of women than it did of men. She recalled working as the first female career-track employee from Doshisha University at Nissay.

Bun: ‘Among the regular employees (sōgōshoku) in my department, all my colleagues were men, and there was only one other woman in the same department’.

Bun also mentioned watching the struggle of a senior regular employee working in a neighbouring section of Nissay.

Bun: ‘The only other woman was my senpai, who was moved to work in Tokyo from Osaka. Because her family remained in Osaka, she would have to take the Shinkansen every weekend to go home to her children, breastfeed, freeze it all, and then go back to work. I was shocked at how hard she was working just to keep her career.’

Maybe influenced by this experience, Bun climbed the career ladder tactically. By entering the entrepreneurial sphere through her first company - an e-commerce business called Littlemoon - she was able to work more flexible hours at home while she raised her children. While easier than working full time in an office, challenges still persisted.

Bun: ‘I gave up everything. I didn’t watch TV at night. I started getting up at 4am, and I gave up shopping, self-care, my hobbies. I just read picture books to my kids, and made sure I could take them to the park. I sacrificed everything for my business except my family. For men, it is not the same.’

👩⚖️ Yumiko Terada: Understanding Gendered Divisions in Legal Practice

Terada also highlighted how women in demanding jobs face a higher workload simply because of their gender. Terada presented her own document containing statistical analysis of the gender gap within the Japanese legal system, with specific reference to 2019 data from The Japan Finance Corporation.

The data does reveal a stark gender imbalance in household labor. Married men spend 1.24 hours on housework daily, while their wives spend 5.51 hours.10 Conversely, married women dedicate 3.07 hours to housework, while their husbands contribute only 1.49 hours.11 This disparity extends to childcare, where women bear approximately 74% of responsibilities compared to men’s 26%.12

In addition, there is a sharp gender pay gap between male and female lawyers, particularly as they get older. The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) reports that while there are smaller gaps between men and women among younger cohorts of lawyers, there are large differences in mid-career and senior cohorts, even ‘among those with the same years of experience’.13 According to the JFBA, this is attributive to the concentration of ‘high earning positions’ among men.14

Terada elaborated on this point.

Terada: ‘Female lawyers primarily handle family law and cases for less affluent clients, while male lawyers more often represent companies and handle high-value cases like corporate litigation. People tend to view female lawyers as more emotional, while male lawyers are perceived as more business-focused. Being assigned such a narrow practice area is harder to escape later in women’s careers’.

Terada herself is a self-described ‘pioneer’ as a female lawyer in the field of supporting entrepreneurs in Osaka. She remembers taking inspiration from a speech during an award ceremony for her work as a mentor for female Japanese youth. This speech, she claimed, moved her to focus on supporting entrepreneurs as a lawyer.

Terada: ‘The U.S. ambassador, Caroline Kennedy, presented an award to a female entrepreneur focused on single mothers. As a recent divorcee myself, I was inspired. I realised entrepreneurship is about finding strengths in people who are often overlooked.’

💫 Untapped Potential and Mottainai women

It is interesting how both Bun and Terada view women as ‘overlooked’ in the corporate sphere. In particular, Bun applies the concept of mottainai, used to describe the untapped potential of ‘waste’ food in Losszero’s mission, to a similar underutilised potential of female leaders.

On a surface level, Japan is trying to improve this situation. The 2024 Basic Policy on Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women (BPGEEW) aims to accelerate women’s participation by 30% in corporate, economic and policymaking fields by 2030. While the BPGEEW vaguely ‘promotes’ women’s participation, there is no public document that explicitly mandates this 30% legal target for TSE firms. Other initiatives like this have also received wide spectator criticism Research by Nakajima, Shirasu and Kodera examines “tokenism”—the practice of making only symbolic efforts to appear inclusive—following Japan’s Corporate Governance Code introduction.15 Tokenism occurs when companies superficially comply with diversity requirements without meaningful inclusion, such as when firms ‘appoint a male outside director first and a female director later as a token’.16 This creates an illusion of progress while maintaining traditional power structures.

🤝 The Importance of Community and Mentorship

Rather than relying on seemingly optional and ‘tokenistic’ top-down initiatives, it might be valuable to consult women who have actually overcome these challenges, like Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada.

Bun: ‘I think it is important to find community. If there was a network for women to talk with other women - either who are established in their careers, or have the same ambitions and issues - then climbing the corporate ladder might be more accessible.’

Terada shared a very similar view, drawing on her experience as a mentor.

Terada: ‘I realised the critical need for female mentors when working with university students in an entrepreneurship program. One talented young woman developed a business idea to place clothing boutiques next to daycare centers, allowing mothers to browse and feel normal for 5-10 minutes while picking up their children. I thought it was brilliant, and my female friends agreed they would use such a service. However, all the other mentors were male, and they unanimously told her they didn’t see a market for the idea. The young woman became discouraged and changed her business concept.’

Community, connection and representation appear to be crucial for Japanese women aspiring to excel in the corporate world. Therefore, it might be argued that even if government initiatives like BPGEEW are somewhat tokenistic, seeing other women in leadership positions might have the power to inspire and create pathways for younger generations. However, this potential progress depends entirely on the extent of ‘tokenism’ across companies. If traditional male power structures persist beneath the surface appearance of female leadership, women may be systematically prevented from making genuine advances into leadership positions. It might be suggested that top-down initiatives to improve gender diversity need to begin with the input of women like Bun and Terada, who can help to overcome the issue of ‘tokenism’, build authentic communities and nurture young women into the lead.

💪 Understanding ‘Joshiryoku’: The Contradiction of Girl Power in Japan

An essential aspect to examine is how female empowerment manifests in Japanese society, particularly what it represents for Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada. Research into this topic reveals the concept of ‘joshiryoku’. The Japanese term ‘joshiryoku’, while literally translating into English as girl (’joshi’)’ and power (’ryoku’), does not particularly invoke a sense of a strong, independent woman in Japanese society. Instead, it is largely viewed as a controversial, often patriarchal term, generally connoting a submissive woman who prioritises ‘developing women’s skills’ and practicing ‘feminine hobbies’.17 Interviews with Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada - both pioneer women in stereotypically male careers - revealed a clear divide between ‘joshiryoku’ and Western understandings of ‘girl power’.

When asked about ‘joshiryoku,’ both Bun and Terada responded with visible confusion and began to laugh. It seemed a shock that the term was being mentioned in the context of the corporate world. This in itself speaks volumes.

Bun: ‘I’ve never been too concerned with my ‘joshiryoku’. I am tall and strong, so I guess cutting out ‘joshiryoku’ was never a problem. If men - most of my business meetings are with men - do not see you as having ‘joshiryoku’, they tend to be less attracted to you and therefore take you more seriously. I haven’t been concerned about my femininity for a long time’.

Based on this, Japan appears to maintain rigid distinctions between gender roles. It is somewhat disappointing how nonchalantly Bun has downplayed her femininity to earn professional respect from her colleagues. However, in a culture where the character for ‘male’ (’男’) contains the element ‘力’ (chikara), meaning strength or power, it’s no wonder that women in leadership roles feel pressure - unconsciously or otherwise - to appear more masculine.

Terada agreed that she both unconsciously and strategically downplays her femininity.

Terada: ‘I think it is an unconscious thing. I don’t notice myself doing it, but I’m sure I do. Sometimes with sensitive issues, I do find it strategic to have a man voice my opinion to a group of other men. It’s not necessarily negative - it’s about finding effective ways to communicate without causing offence.’

👩💼 Navigating Femininity in Corporate Settings

Regarding both interviewee’s rather casual dismissal of their femininity in the professional sphere, it is safe to say that they are simply playing the hand they have been dealt. After all, they have both recognised the adaptability required by the role of a woman in the higher ranks of the corporate world, and, as pioneers, they have faced the brunt of society’s expectations.

Is there a better Japanese term that connotes ‘girl power’ in more ways than just translation? Not yet, it seems. However, it seems that the term ‘female entrepreneur’ is inspiring in itself. Losszero employee Sawaka Yamaguchi spoke on the importance of role models.

Yamaguchi: ‘As a woman myself, [Mitsuki Bun] is my inspiration, my role model. I am so grateful to be able to feel her so closely and learn from her. [Losszero] is not a big company, so it is unusual for me to have such a close relationship with the CEO’.

Hearing this, it is clear that girl power, or female empowerment, is markedly different from ‘joshiryoku’. Lisa Matsumoto’s piece in Metropolis Japan magazine summarises it perfectly: while ‘girl power speaks to what a girl can do,’ Joshiryoku speaks to ‘what a girl must do’.18 Mitsuki Bun and Yumiko Terada seem to have effectively broken past the joshiryoku ‘obligation’ that Japanese society pressures women to fulfil, and have provided inspiring examples for future generations who wish to follow in their footsteps.

🔍 Conclusion: Navigating Progress in a Complex Landscape

Through the candid experiences of Bun and Terada, we gain valuable insights into the complex challenges faced by female leaders in Japan’s corporate landscape. Their stories highlight how systematic barriers, traditional gender expectations, and the concept of “joshiryoku” continue to shape women’s professional trajectories. Despite these obstacles, both women have demonstrated resilience, sacrifice and adaptability when navigating male-dominated environments.

What emerges most clearly from these interviews is the critical importance of representation and community. As both Bun and Terada emphasised, creating networks where women can support each other and having visible female role models are essential for meaningful change. Their success stories serve not just as individual achievements but as powerful counter-narratives to Japan’s persistent gender gap. A recent real-world example of community among female entrepreneurs can be seen in the BWA pitch conference, which former SIIFIC intern Lily Thomas covered in detail. Click here to read more.

While government initiatives like BPGEEW represent steps in the right direction, true transformation will require deeper cultural shifts and practical support systems for women in leadership. The journeys of pioneers like Bun and Terada suggest that progress, though slow and demanding significant personal sacrifice, is indeed possible. Their redefinition of female empowerment in Japan’s corporate world offers hope that future generations of women may face fewer barriers and more opportunities to lead on their own terms.

World Economic Forum. (2025). Global Gender Gap Report 2025. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2025/

Ibid.

Female executives at Japan’s prime section firms reach 18.4%. (2025, October 2). Nippon.com. https://www.nippon.com/en/news/yjj2025100200805/

Ibid.

SIIFIC. (2025, September 5). Who is investable and why. SIIFIC Substack. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://siific.substack.com/p/who-is-investable-and-why

Japan Finance Corporation. (2013). 女性経営者の実態と意識に関する調査 [Survey on the situation and awareness of women business owners]. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://www.jfc.go.jp/n/findings/pdf/soukenrepo_13_06_03.pdf

Ministry of the Environment, Japan. (2023). MOE Japan Discloses the Estimated Amount of Japan’s Food Loss and Waste Generated in FY2023. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://www.env.go.jp/en/press/press_00002.html#:~:text=1.,19 of 2019

Calder-Wang, S., & Gompers, P. A. (2021). And the children shall lead: Gender diversity and performance in venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 143(2), 915-941. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X21001483

IFC. (2019). Moving toward gender balance in private equity and venture capital. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doclink/2019/report-moving-toward-gender-balance-in-private-equity-and-venture-capital.pdf

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. (2020). Time use by gender and marital status. Journal of Labor Policy, 9, 68-77.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Japan Federation of Bar Associations. (2018). 弁護士白書 2018 年版:特集「弁護士会の男女共同参画は進んだか」 [Lawyer White Paper 2018: Feature “Has Gender Equality Progressed in Bar Associations?”]. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://www.nichibenren.or.jp/library/ja/jfba_info/statistics/data/white_paper/2018/1-6-1_tokushu_all.pdf

Ibid.

Nakajima, K., Shirasu, Y., & Kodera, E. (2025). Tokenism in gender diversity on board of directors. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 75, Article 101342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2024.101342

Ibid.

Kokoro Research Center. (2023). Understanding the women’s empowerment movement in Japan: A historical perspective. Kyoto University. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://kokoro-jp.com/columns/1620/

Matsumoto, L. (2023). Last word: Joshiryoku. Metropolis Japan. Retrieved October 9, 2025, from https://metropolisjapan.com/last-word-joshiryoku/